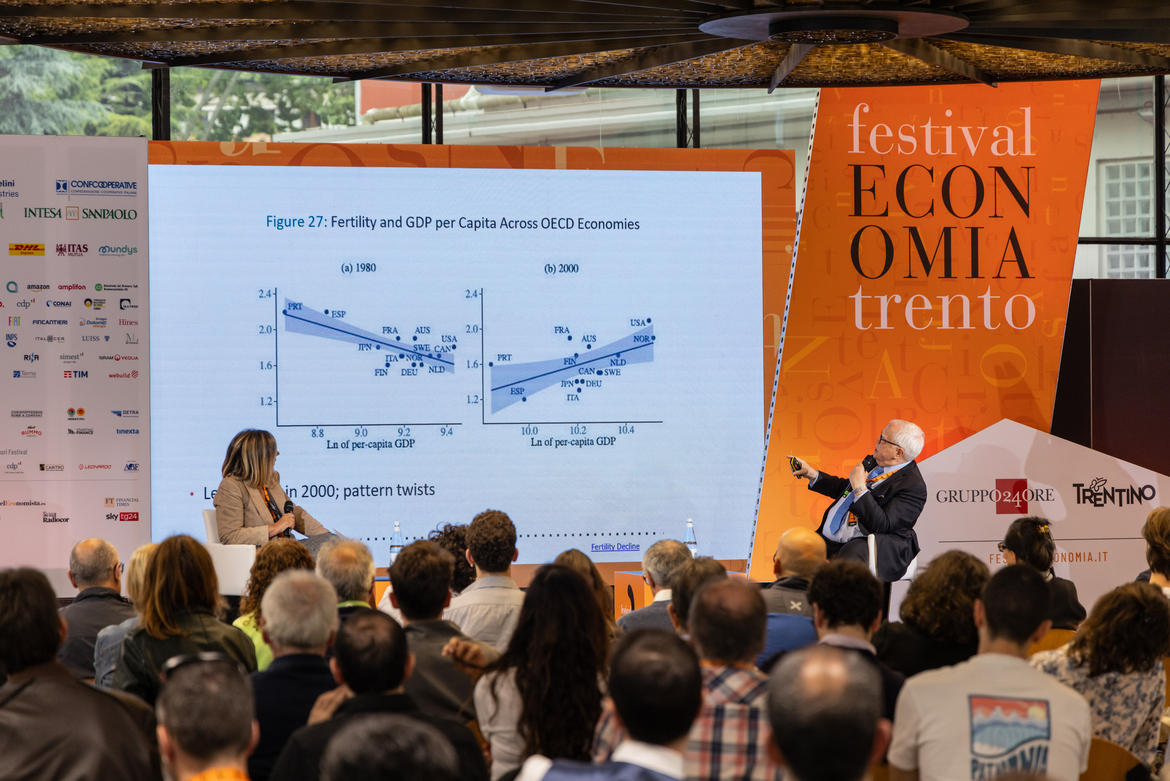

At the 2025 Trento Festival of Economics, the lecture on declining fertility offered a comprehensive overview of global demographic trends. Fertility rates have fallen below replacement levels across most of the world, with only a few exceptions, most notably on the African continent. Historical models, like Malthus’ theory linking fertility to food supply, have given way to modern frameworks that emphasize education, income, and female autonomy. Factors like delayed marriage, greater labor market participation, and shifting household dynamics have contributed to lower and later fertility. The discussion highlighted the need to recognise the value of caregiving, reduce the “child penalty”, and rethink the institutional support for families.

James Heckman examined the long-term decline in fertility rates globally, with a specific focus on Italy and other advanced economies. Since 1950, the total fertility rate has fallen well below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman in most of the world, with some exceptions. Italy has been under this threshold since 1978. Historically explained by Malthusian dynamics, according to which population growth is linked to food supply and follows cycles of expansion and collapse, fertility decline is now better understood through changes in public health, education, and gender roles. “The major phenomenon we need to understand is the bargaining power of women”, argued the Nobel Laureate, highlighting how female autonomy, delayed childbirth, and increased participation in the labour market have reshaped fertility decisions. Factors such as the “child penalty” and inequality within and between households further influence trends. As he noted, “women might want children, if society helps.”

In the Q&A session, the conversation moved from fertility trends to broader policy challenges. James Heckman underlined that even in high-fertility regions, such as parts of Africa, rates are declining as traditional household roles evolve. On Europe’s competitiveness, he called for a regulatory “revolution”, arguing that “the level of regulation is so great that it slows down innovation”. To support fertility and sustain welfare systems, he stressed the need to recognise the social value of motherhood and rethink how societies support families.